Florian's RTF Blog

Sunday, November 7, 2010

PO-PO-PO-PO-PO-PO-POWER

The recent series of Old Spice body wash commercials is a great example of an ad campaign that is effective in several ways. The commercials employ an offbeat humor that is equally arresting, hilarious, and memorable (simply for its weirdness), plus they star Terry Crews, a very recognizable, mainly comic actor. The repeated, bellowed catchphrases help too: anyone who has seen one or more of the commercials at least a few times will remember that "OLD SPICE BODYWASH HAS 16 HOURS OF ODOR BLOCKING POWWW EEERRRRRRRRRRRRR!!!!!!!"

The main appeal of the commercial is hyperbole, or exaggeration. Ads that use this tactic take the benefits or uses of the product and exaggerate them, sometimes slightly or subconsciously and sometimes so overtly that it becomes humorous (most of the time the humor is intentional), like the AXE commercials that depict AXE users becoming literal chick magnets, or the new McRib commercial that shows people eating the McRib and experiencing a pleasure so intense it borders on orgasmic. The unspoken message of this appeal is either "if you buy our product, you to can experience these awesome benefits!"or alternately "the capabilities of this product are so strong they're pretty much magical."

The Old Spice commercial employs the second of these two messages within the appeal of exaggeration. With claims like "Old Spice bodywash is so powerful it can block out the sun! But then it gets too cold, so it makes another sun!", that are obviously exaggerated in humorous way, the commercial appeals to the viewer's funny bone rather than their rational side. Yet then we may think, they make this point so aggressively that it probably has some basis in truth. Still, what we retain is the humor of the exaggeration, making the commercial and thus the product name firmly lodged into our minds as consumers.

Sunday, October 31, 2010

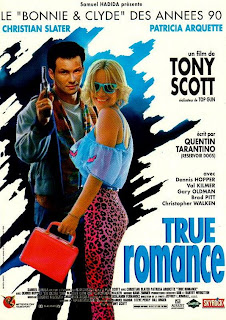

3-Act Structure in True Romance

The film True Romance adheres to the traditional hollywood 3-act structure very well. In the first act, we are introduced to the main characters and their situation: Clarence, a lonely comic book store clerk meets Alabama, a breezy call girl and they fall in love. They are married 17 minutes into the movie, the quickness of which sets the pace for the rest of the film. The first act peaks at a major plot point when Clarence kills Drexl, Alabama's pimp, and takes a suitcase which he believes to be full of her personal items, but is actually full of cocaine (about 30 minutes in). This advances & complicates the plot in 2 ways: first, it presents the central "mission" of Clarence and Alabama: they decide to go to California and sell the cocaine in bulk with the hopes of eventually starting a new life together with the money. Second, the missing cocaine prompts a group of Sicilian gangsters, Drexl's superiors, to hunt down Clarence and Alabama and retrieve their drugs.

In the second act, the plot is further developed as Clarence meets his friend, an aspiring actor named Dick who lives in California, whose contact Elliot can connect Clarence to Lee Donowitz, a big-time movie producer to whom he plans to sell the cocaine. About an hour long, the second act takes its time with scene progression and is slightly slower-paced than the first. Clarence and Alabama visit Clarence's dad, an ex-cop, to make sure they aren't being followed by the police because of Drexl's death. They find out they are in the clear, make merriment, and go on to California. Soon the Sicilian gangsters are introduced as they show up in Clarence's dad's trailer, demanding the whereabouts of Clarence and Alabama and eventually killing Clarence's dad. Once in California, Clarence and Alabama have a series of meet-ups with Dick and Elliot, eventually setting up a deal with Donowitz. There are a few more plot points in the second act that escalate the film's conflicts dramatically: First, one of the gangsters shows up in Clarence and Alabama's motel room and finds Alabama there alone, he beats her into submission and almost kills her, but she luckily gets the upper hand, takes a mozart bust and bashes his head in with it. This brings knowledge of the gangsters' pursuit to Clarence, who decides to bring a gun to the meeting with Donowitz, just in case. Second, soon before the meeting, Elliot is arrested for cocaine possession, and after interrogation reveals the planned drug deal to the cops. They get him to wear a wire at the meeting, planning to burst in and arrest everybody once sufficient evidence has been obtained.

The 3rd act and climax of the film is the drug deal scene in Donowitz' hotel room, about 30 minutes long. Here is the peak of the conflict, where all of the opposing forces in the film come together. All the major characters, protagonists and antagonists, are present, Clarence, Alabama, Dick, Elliot (wearing the wire), Donowitz, and 2 armed guards inside the hotel room, the cops listening in from a lower floor, and the sicilian gangsters on their way through the hotel. There is a period of calm before the storm as Clarence and Donowitz talk, bonding over their mutual love of badass cinema. The deal is made, and the cops and gangsters burst in at the same time, setting off a massive shootout. Dick flees and everyone but Clarence and Alabama are killed, although Clarence sustains a gunshot wound to the eye. The two of them make their way out of the hotel with the money, avoiding the masses of police outside. They are shown later on a beach in Cancun with a baby, having resolved their conflicts and achieved their goal in the film, in a "happily ever after" scene.

In the second act, the plot is further developed as Clarence meets his friend, an aspiring actor named Dick who lives in California, whose contact Elliot can connect Clarence to Lee Donowitz, a big-time movie producer to whom he plans to sell the cocaine. About an hour long, the second act takes its time with scene progression and is slightly slower-paced than the first. Clarence and Alabama visit Clarence's dad, an ex-cop, to make sure they aren't being followed by the police because of Drexl's death. They find out they are in the clear, make merriment, and go on to California. Soon the Sicilian gangsters are introduced as they show up in Clarence's dad's trailer, demanding the whereabouts of Clarence and Alabama and eventually killing Clarence's dad. Once in California, Clarence and Alabama have a series of meet-ups with Dick and Elliot, eventually setting up a deal with Donowitz. There are a few more plot points in the second act that escalate the film's conflicts dramatically: First, one of the gangsters shows up in Clarence and Alabama's motel room and finds Alabama there alone, he beats her into submission and almost kills her, but she luckily gets the upper hand, takes a mozart bust and bashes his head in with it. This brings knowledge of the gangsters' pursuit to Clarence, who decides to bring a gun to the meeting with Donowitz, just in case. Second, soon before the meeting, Elliot is arrested for cocaine possession, and after interrogation reveals the planned drug deal to the cops. They get him to wear a wire at the meeting, planning to burst in and arrest everybody once sufficient evidence has been obtained.

The 3rd act and climax of the film is the drug deal scene in Donowitz' hotel room, about 30 minutes long. Here is the peak of the conflict, where all of the opposing forces in the film come together. All the major characters, protagonists and antagonists, are present, Clarence, Alabama, Dick, Elliot (wearing the wire), Donowitz, and 2 armed guards inside the hotel room, the cops listening in from a lower floor, and the sicilian gangsters on their way through the hotel. There is a period of calm before the storm as Clarence and Donowitz talk, bonding over their mutual love of badass cinema. The deal is made, and the cops and gangsters burst in at the same time, setting off a massive shootout. Dick flees and everyone but Clarence and Alabama are killed, although Clarence sustains a gunshot wound to the eye. The two of them make their way out of the hotel with the money, avoiding the masses of police outside. They are shown later on a beach in Cancun with a baby, having resolved their conflicts and achieved their goal in the film, in a "happily ever after" scene.

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Patterns in Sitcoms

The Waitress: What do you want, Charlie?

Charlie: I like your bracelet.

The Waitress: Great.

Charlie: That’s one of those, uh, Lance Armstrong, “Race for the Cure”… “Live Strong” kind of things.

The Waitress: Yeahhh.

Charlie: Cool. That’s very cool. You must be a very compassionate person—

The Waitress: I’m not.

Charlie: Uh—

The Waitress: Did you want something from me, or…

Charlie: What time are— are you getting off work? It’s not a… thing to walk away about. Whatever.

Charlie: I like your bracelet.

The Waitress: Great.

Charlie: That’s one of those, uh, Lance Armstrong, “Race for the Cure”… “Live Strong” kind of things.

The Waitress: Yeahhh.

Charlie: Cool. That’s very cool. You must be a very compassionate person—

The Waitress: I’m not.

Charlie: Uh—

The Waitress: Did you want something from me, or…

Charlie: What time are— are you getting off work? It’s not a… thing to walk away about. Whatever.

Charlie Kelly's infatuation with the Waitress is a good example of a pattern that serves both of these purposes within It's Always Sunny In Philadelphia. There are multiple episodes where Charlie tries to charm the Waitress, with differing levels of success (that all ultimately end up in failure). He tries to impress her by volunteering to become a ref in a children's basketball league, gain her pity by feigning cancer, among many other half-baked, doomed attempts to win her affection. The humor in the relationship between these characters is the irony that we, the audience, know that Charlie will always fail because the waitress hates him (and is actually attracted to Dennis, Charlie's "friend"), although this does nothing to stop Charlie's repeated, comically hopeless efforts.

Above:

http://itsalwayssunny.tumblr.com/post/213311084/the-waitress-what-do-you-want-charlie-charlie

Sunday, October 17, 2010

Shots of Heroin

Around 30 minutes into the film Trainspotting, the characters Spud, Sick Boy and Renton make a "healthy, informed, democratic decision to get back on heroin as soon as possible." What follows is a montage exploring the characters' drug use the lifestyles they subsequently lead. Of course the most direct image in this series is an extreme close-up of a spoon in which heroin is mixed, cooked, and sucked into a syringe. This shot provides a defining focus of the interconnected images of the characters, as it is the singularity that their lives revolve around. The extreme closeup presents heroin directly and absolutely, providing the one of the centralizing images that runs throughout the film.

Another shot is a low-angle long shot of Sick Boy, standing over Renton after having presumably shot up heroin, explaining the importance of Ursula Andress to the James Bond series. This shot empowers Sick Boy in an ironic way, partly showing his inflated ego and sense of elevation over the other characters, justified by a perhaps superior intellect and an impressive familiarity with Sean Connery films.

When Tommy asks Renton if he can try heroin for the first time after being dumped by his girlfriend, his discourse is presented by a medium shot, from a slight low angle. This places emphasis on his facial expressions/emotions and body language, which when combined with the murky lighting of the scene show a sense of sadness and desperation that has led him to make the decision to try heroin.

image:

http://www.husar.us/blog/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/trainspotting.jpg

Another shot is a low-angle long shot of Sick Boy, standing over Renton after having presumably shot up heroin, explaining the importance of Ursula Andress to the James Bond series. This shot empowers Sick Boy in an ironic way, partly showing his inflated ego and sense of elevation over the other characters, justified by a perhaps superior intellect and an impressive familiarity with Sean Connery films.

When Tommy asks Renton if he can try heroin for the first time after being dumped by his girlfriend, his discourse is presented by a medium shot, from a slight low angle. This places emphasis on his facial expressions/emotions and body language, which when combined with the murky lighting of the scene show a sense of sadness and desperation that has led him to make the decision to try heroin.

image:

http://www.husar.us/blog/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/trainspotting.jpg

Thursday, October 7, 2010

Hollywood Classique, Le Système des Vedettes, et Film Noir

One defining aspect of how the Hollywood studio system in the 1930s and 1940s produced its films was the repeating use and promotion of films through star actors. In many cases, the pure celebrity of names like Humphrey Bogart, Mary Pickford or James Cagney would draw audiences to a film more effectively than the film itself. As a result of this practice, many stars would be typecast into similar roles in similar films multiple times, and studios would churn out movies of the same genre repeatedly using these star-driven characters as templates. The tough, dark, anti-hero private eye is a perfect example of this effect, as such a character type was central to the development of the film noir genre. Humphrey Bogart exemplified this type of character, playing private investigator Sam Spade in the genre-defining The Maltese Falcon, then Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep. His star power and that of similar actors like Robert Mitchum were a driving force behind film noir, a genre whose power and impact can be seen even today, as it is frequently referenced and modeled in contemporary media by the likes of Calvin and Hobbes.

images:

http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/files/2008/07/gun1.jpg

http://webspace.webring.com/people/lm/mbarton/bullet.jpg

Sunday, October 3, 2010

All In The Family vs Family Guy

All In The Family is an iconic example of 1970s formulaic family-based sitcom television. It was a pioneer in controversial TV, due to the often comically bigoted nature of Archie Bunker, one of the central characters. Through him critical issues such as politics, racial issues, and homosexuality were addressed in a way that no other sitcoms had previously. Nowadays it seems these themes, which would have been incendiary in earlier years, are ubiquitous in TV. A new breed of family sitcom that has spawned out of the exploration of these themes is the animated family sitcom, one of the best examples of which is Family Guy. This show raises contemporary issues constantly, including issues of sexual orientation, drug use, censorship, and religion, among many others. However, the manner in which they are addressed are entirely different from All In The Family. Family Guy heavily satirizes its subjects by creating caricatures out of them, using extreme hyperbole to create parody, revealing their absurdity in a similar fashion that Archie Bunker's exaggerated bigotry serves as a pedestal/hot plate for these issues. Both shows present controversial issues using parody, however Archie's existence as a vehicle for critique is much more intentional (although perhaps not widely received by its audience) than Family Guy's style of extreme parody that frequently borders upon the absurd (but, for the most part, retains its humor).

images:

http://www.free-extras.com/images/peter_griffin-1115.htm

http://nationallampoon.com/files/2009/05/15-archie-bunker.jpg

images:

http://www.free-extras.com/images/peter_griffin-1115.htm

http://nationallampoon.com/files/2009/05/15-archie-bunker.jpg

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Radio and Technology

One of the central forces that aided the growth, rise to prominence and widespread dissemination of radio (and radio culture) was the constant improvement of radio technology from its inception to the present.

In practically every area of the media, the force of technological change is responsible for large-scale improvement and increased accessibility by the public. What technology ultimately strives to do is to reduce the need for human effort in exchange for increased efficiency and flexibility, thus making any medium easier to utilize and spread amongst the populace. The Internet is perhaps the best example of this, as recent online innovations like iTunes, Hulu, and Netflix have revolutionized music, television, and home video respectively, each by bringing their intended service directly to the consumer’s home with increased speed, efficiency, and ease.

With respect to radio, technological innovations are what made the medium into the widely appreciated media giant it has become. This is due to the nature of radio as one of the earliest wireless mediums that could be broadcast directly into the home. When Gugliermo Marconi created the wireless telegraph, which was the first machine to use radio waves to broadcast messages wirelessly, it was restricted in the sense that it could only transmit messages through the medium of Morse code. Later, when Lee de Forest’s vacuum tube was applied to this technology, it enabled the transmission of sound, opening radio’s potential to broadcast music, talk shows, and ads to home receivers. With such technology in place, all it took was the ideas of men like David Sarnoff, who predicted radio’s status as a household utility, to launch the long and evolving phenomenon that it has become.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)